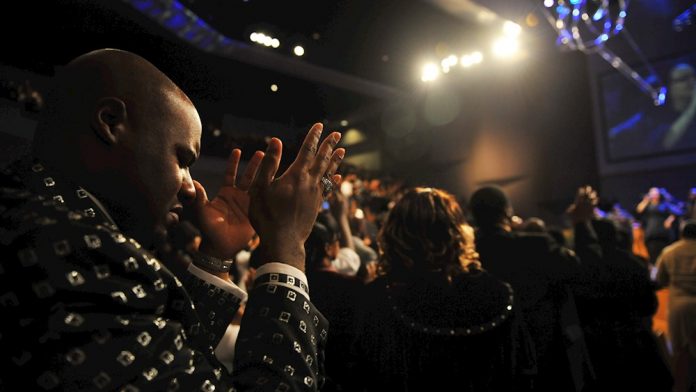

When deciding to close the doors of black churches, congregational leaders across the US wrestle with unique considerations. Paul J. James, pastor of CareView Community Church in Lansdowne, Pennsylvania, noted in an interview with The Undefeated how closing is “counterintuitive to most churches, especially the black church… where we’re just glad to get together because of how hard life has been historically for us here in America. Church has been a safe place for us. It’s been a safe harbor. Now here we are faced with the inability to come together.”

Last week, the federal government strongly urged Americans not to gather in groups of more than 10, and restrictions keep coming. We suspect that many churches will close in the near future, but the decision will not been easy.

In St. Louis, the mayor hosted a teleconference with 300 clergy, including many of black churches, to urge them not to hold services. While some chose to stop meetings and modify their ministries, others struggled to make the change.

In Michigan, Gov. Gretchen Whitmer banned gatherings of more than 50 but then exempted churches from penalties. This will give some churches more options, though many are choosing to modify in some way. Triumph Church, which has seven locations in the Detroit area, will continue to gather in person, for now, though it expanded the number of services to reduce congregation size and is asking members to register ahead of time so it can maintain at least six feet between worshippers. It is also providing an online service and a drive-in service.

A lot of things inform these responses to the coronavirus outbreak: culture, histories of discrimination, and marginalization, as well as faith-based values. People experience events like COVID-19 not only as individuals but also in communities and in the social locations we inhabit. As social scientists—Deidra as a black woman doing research on HPV and Elaine as a white woman who studies how religious organizations respond to science—we offer some observations based on our research for the past 10 years at the Religion and Public Life Program at Rice University. We have been gathering upwards of 150 religious and civic leaders regularly to talk about how we can use social science research on religion to build common ground for the common good.

Among the congregations we have checked in with during the past two weeks, it seems to us that in our city of Houston, Texas, black churches, in particular, have continued to gather in person. In our city, Windsor Village United Methodist Church, which has about 16,000 members, and Good Hope Missionary Baptist Church, which has more than 2,500, both initially responded with statements informing members that while they would be exercising precautions, they would still be holding corporate worship services. They have since modified their approaches: Windsor Village transitioned to all virtual services last Sunday; Good Hope met for corporate worship while requiring adjusted practices, such as liberal hand washing and greeting by waving instead of hand shaking.

In African American communities where “Go Down, Moses” is commonly sung, a unique history of knowing God as protector and deliverer means faith, not fear, in the midst of this pandemic.

But pastors are now being forced to exercise a different kind of faith—trusting God as provider in the midst of financial and other kinds of threats, as they are having to make the difficult decision of closing church doors in order to protect the flock within communities that deeply prioritize collective strength and uplift.

Social scientist of religion Cleve V. Tinsley IV says that “There are multiple reasons these large mega-churches may keep their doors open, reasons that relate to a complex web of fear of paying large mortgages and staff salaries, smaller black churches collapsing because of lack of institutional and financial support; they also may not have the kind of larger structural resources to maintain their buildings that some mainline churches have when their doors close and giving inevitably drops off.

“There also may be differences between older and younger generations of black Americans. Those who have been through Jim Crow may go to church no matter what. We need to be considering the structural, economic, and generational divides that shape responses to COVID-19,” said Tinsley.

Public health scholars also offer the Health Belief Model to explain why some might continue to meet despite public health warnings. The model suggests that people engage in health-promoting behaviors, such as social distancing, when perceived threat of a disease is high (meaning preventive action is the product of one’s perceived susceptibility of contracting a disease as well as their beliefs about the severity of it). For some black Americans—and many other Americans—myths about immunity to COVID-19 coupled with WHO reports that 80 percent of the cases are “mild” might factor into the equation.

Source: Christianity Today

All Content & Images are provided by the acknowledged source