LONDON — Before the pandemic, a traditional state of play prevailed in the enormous economies on the opposite sides of the Atlantic. Europe — full of older people, and rife with bickering over policy — appeared stagnant. The United States, ruled by innovation and risk-taking, seemed set to grow faster.

But that alignment has been reordered by contrasting approaches to a terrifying global crisis. Europe has generally gotten a handle on the spread of the coronavirus, enabling many economies to reopen while protecting workers whose livelihoods have been menaced. The United States has become a symbol of fecklessness and discord in the face of a grave emergency, yielding deepening worries about the fate of jobs and sustenance.

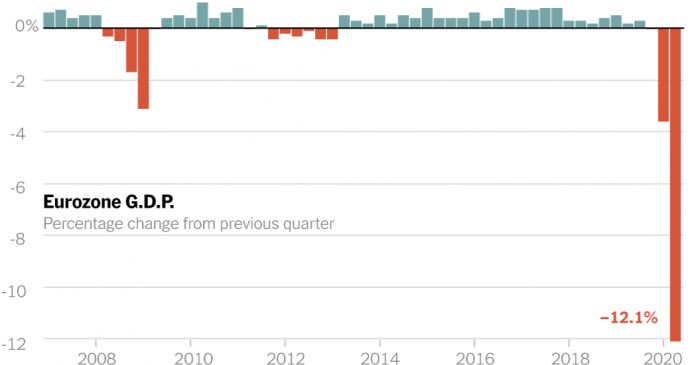

On Friday, Europe released economic numbers that on their face were terrible. The 19 nations that share the euro currency contracted by 12.1 percent from April to June from the previous quarter — the sharpest decline since 1995, when the data was first collected. Spain fell by a staggering 18.5 percent, and France, one of the eurozone’s largest economies, declined 13.8 percent. Italy shrunk by 12.4 percent.

Europe appeared even worse than the United States, which the day before recorded the single-worst three-month stretch in its history, tumbling by 9.5 percent in the second quarter.

But beneath the headline figures, Europe flashed promising signs of strength.

Germany saw a drop in the numbers of unemployed, surveys found evidence of growing confidence amid an expansion in factory production, while the euro continued to strengthen against the dollar as investment flowed into European markets — signs of improving sentiment.

These contrasting fortunes underscored a central truth of a pandemic that has killed more than 670,000 people worldwide: The most significant cause of the economic pain is the virus itself. Governments that have more adeptly controlled its spread have commanded greater confidence from their citizens and investors, putting their economies in better position to recuperate from the worst global downturn since the Great Depression.

“There is no economic recovery without a controlled health situation,” said Ángel Talavera, lead eurozone economist at Oxford Economics in London. “It’s not a choice between the two.”

European confidence has been bolstered by a groundbreaking agreement struck in July within the European Union to sell 750 million euro ($892 million) worth of bonds that are backed collectively by its members. Those funds will be deployed to the hardest hit countries like Italy and Spain.

The deal transcended years of opposition from parsimonious northern European countries like Germany and the Netherlands against issuing common debt. They have balked at putting their taxpayers on the line to bail out southern neighbors like Greece while indulging in crude stereotypes of Mediterranean profligacy. The animosity perpetuated the sense that Europe was a union in name only — a critique that has been muted.

The United States has spent more than Europe on programs to limit the economic damage of the pandemic. But much of the spending has benefited investors, spurring a substantial recovery in the stock market. Emergency unemployment benefits have proved crucial, enabling tens of millions of jobless Americans to pay rent and buy groceries. But they were set to expire on Friday and there were few signs that Congress would extend them.

Europe’s experience has underscored the virtues of its more generous social welfare programs, including national health care systems.

Americans feel compelled to go to work, even at dangerous places like meatpacking plants, and even when they are ill, because many lack paid sick leave. Yet they also feel pressure to avoid shops, restaurants and other crowded places of business because millions lack health insurance, making hospitalization a financial catastrophe.

“Europe has really benefited from having this system that is more heavily dominated by welfare systems than the U.S.,” said Kjersti Haugland, chief economist at DNB Markets, an investment bank in Oslo. “It keeps people less fearful.”

The more promising situation in Europe is neither certain nor comprehensive. Spain remains a grave concern, with the virus spreading, threatening lives and livelihoods. Italy has emerged from the grim calculus of mass death to the chronic condition of persistent economic troubles. Britain’s tragic mishandling of the pandemic has shaken faith in the government.

If short-term factors look more beneficial to European economies, longer-term forces may favor the United States, with its younger population and greater productivity.

A sense of European-American rivalry has been provoked by the bombast of a nationalist American president, making the pandemic a morbid opportunity to keep score.

“There is a certain amount of triumphalism,” said Peter Dixon, a global financial economist at Commerzbank in London. “People are saying, ‘Our economy has survived, we are doing OK.’ There’s a certain amount of European schadenfreude, if I can use that word, given everything that Trump has said about the U.S.”

But for now, Europe’s moment of confidence is palpable, most prominently in Germany, the continent’s largest economy.

Though the German economy shrank by 10.1 percent from March to June — its worst drop in at least half a century — the number of officially jobless people fell in July, in part because of government programs that have subsidized furloughed workers.

Surveys show that German managers — not a group inclined toward sunny optimism — have seen expectations for future sales return to nearly pre-virus levels. That buoyancy translates directly into growth, emboldening companies to rehire furloughed workers.

Ziehl-Abegg, a maker of ventilation systems for hospitals, factories and large buildings, recently broke ground on a 16 million euro ($19 million) expansion at a factory in southern Germany.

“If we wait to invest until the market recovers, that’s too late,” said Peter Fenkl, the company’s chief executive. “There are billions of dollars in the market ready to be invested and just waiting for the signal to kick off.”

The euro has gained more than 5 percent against the dollar so far this year, according to FactSet. European markets have been lifted by international money flowing into so-called exchange-traded funds that purchase European stocks. The Stoxx 600, an index made up of companies in 17 European countries, appears set for a second straight month of gains outpacing the S&P 500.

The French oil giant Total saw demand for its products in Europe drop by nearly one third in the second quarter of the year, but a powerful recovery has been gaining momentum, said the company’s chairman and chief executive, Patrick Pouyanné.

“Since June, we have seen a rebound here in Europe,” he said during a call with analysts. “Activity in our marketing networks is back to, I would say, 90 percent of the pre-Covid levels.”

France, Europe’s second largest economy, has been buttressed by aggressive government spending. President Emmanuel Macron has mobilized more than 400 billion euros ($476 billion) in emergency aid and loan guarantees since the start of the crisis, and is preparing an autumn package worth another 100 billion euros.

Those funds paid businesses not to lay off workers, allowing more than 14 million employees to go on paid furlough, stay in their homes, accumulate modest savings and continue spending. Delayed deadlines for business taxes and loan payments spared companies from collapse.

In the second quarter, when France was still partially locked down, the country’s economy contracted by nearly 14 percent. Tourism, retail and manufacturing, the main pillars of the economy, ground to a halt.

But services, industrial activity and consumer spending have all shown signs of improvement. The Banque de France, which originally expected the economy to shrink more than 10 percent this year, recently forecast less damage.

In Spain, a sense of recovery remains distant. Its economy shrunk by nearly 19 percent from April to June. The nation’s unemployment rate exceeds 15 percent, and could surge higher if a wage subsidy program for furloughed workers is allowed to expire in September.

Spain officially ended its coronavirus state of emergency on June 21, but has since suffered an increase in infections. The economic impacts have been compounded by Britain’s decision to force travelers returning from Spain to quarantine for two weeks. Tourism accounts for 12 percent of Spain’s economy.

Italy is also highly exposed to tourism. Its industry is concentrated in the north of the country, which saw the worst of coronavirus. The central bank expects the Italian economy to contract by nearly 10 percent this year.

But exports surged more than one-third in May compared with the previous month. That left them below pre-pandemic levels, yet on par with German and American competitors, according to Confindustria, an Italian trade association.

“We are starting to slowly recover after the most violent downfall in the last 70 years,” said Francesco Daveri, an economist at Bocconi University in Milan.

Europe’s fortunes appear on the mend because its people are more likely to trust their governments.

Denmark acted early, imposing a strict lockdown while paying wage subsidies that limited unemployment. Denmark suffered far fewer deaths per capita than the United States and Britain.

With the virus largely controlled, Denmark lifted restrictions earlier, while Danes heeded the call to resume commercial life. The Danish economy is expected to contract by 5.25 percent this year, according to the European Commission, with a substantial improvement in the second half of the year.

In the United States, people have wearied of bewildering and conflicting advice from on high against a backdrop of more than 150,000 deaths.

The result has been record surges of new cases along with a syndrome likely to persist — an aversion to being near other people. That spells leaner prospects for retail, hotels, restaurants and other job-rich areas of the American economy.

Liz Alderman reported from Paris. Emma Bubola contributed reporting from Milan, Raphael Minder from Madrid and Stanley Reed and Eshe Nelson from London.