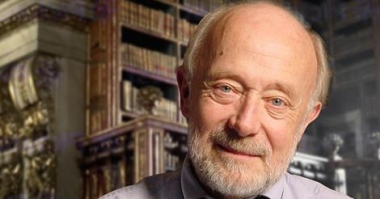

Christian Today report- Liberal theologian Marcus J Borg, who died last week at the age of 72, polarised opinions. The New Testament scholar was both praised for his independent thinking and attempts to make the gospel credible, as he saw it, to the modern age, and vilified for his radical departures from Christian orthodoxy.

He was one of a group of scholars known as the Jesus Seminar, which was very active in the 1980s and 90s and sought to foster a critical approach to Christian origins as they were recounted in the four canonical Gospels and other early material (they rejected the notion that there was anything particularly authoritative about the Bible).

Among other projects, they approached the Gospels with a high degree of scepticism arguing that whereas the pioneers of historical criticism had to argue that something shouldn’t be regarded as factually true, so much more was known today about the shaky foundations of the biblical witness that the onus was on scholars to show that it should. So in The Five Gospels: The Search for the Authentic Words of Jesus (1993) for instance, they evaluated the authenticity of 500 Gospel statements and events by voting with coloured beads in a points-based system.

A red bead meant the voter believed Jesus did say what he is quoted as saying (three points); pink meant he probably said something like it (two points); grey meant it was Jesus-like (one point) and black meant it was a later addition (zero points). Very few sayings or events passed the test.

Borg, like the other Jesus Seminar participants, rejected the miraculous. Jesus, he believed, was a social prophet and reformer, a wisdom teacher and mystic of the same type as Gandhi and Martin Luther King.

An example of his approach is in a piece he wrote for his blog during Advent last year, in which lamented that “Advent and Christmas have virtually been swallowed up by the miraculous”, such as the stories of the visits of angels and the wise men being guided by a star. “To be candid, I do not think that any of this happened,” he wrote. “Of course, there is some historical memory in the stories. Jesus was born. He really lived. He was Jewish. His parents’ names were Mary and Joseph. They lived in Nazareth, a very small peasant village, perhaps as small as a few hundred. But I do not think that there was an annunciation by an angel to Mary, or a virginal conception, or a special star, or wisemen from the East visiting the infant Jesus, or angels filling the night with glory as they sang to shepherds.”

However, he denied being a “debunker” of the stories and said there was a “third way” between regarding them as fact or fable: “Rather, they are early Christian testimony, written roughly a hundred years after Jesus’s birth. They testify to the significance that Jesus had come to have in their lives and experience and thought. The stories are parabolic, metaphorical narratives that can be true without being factual.” Advent and Christmas, he said, “are about the biblical hope and way, the path, to a new kind of world. They are about our rebirth and the world’s rebirth.”

Unlike some other ‘progressive Christians’, he was respected both for his personal spirituality and for his willingness to engage courteously with orthodox believers. The former Bishop of Durham, academic N T Wright, took part in public debates with him and paid tribute to him saying that despite their disagreements, he and Borg shared “a deep and rich mutual affection and friendship”.

Theologian Brian D McLaren wrote: “Hardly the hard-bitten ‘liberal theologian’ out to eviscerate Christianity of any actual faith, he impressed me as a fellow Christian seeking an honest, thoughtful, and vital faith, ready to dialogue respectfully with people who see things differently.”

Borg also wrote on his blog that he sought to be “an evangelist to those in the Christian middle – people who are still in churches but who are troubled by some and perhaps many of conventional Christian beliefs that were taken for granted not so long ago”.

Borg wrote or co-wrote 21 books, one of the most popular of which was Meeting Jesus Again for the First Time. In his last, the memoir Convictions: How I Learned What Matters Most (2014), he wrote: “Imagine that Christianity is about loving God. Imagine that it’s not about the self and its concerns, about ‘what’s in it for me,’ whether that be a blessed afterlife or prosperity in this life.”

It would be ungracious to deny that he brought wisdom and penetration both to biblical scholarship and to the wider theological conversation. However, his work is open to criticism, too. Scholars have generally not found the approach of the Jesus Seminar convincing in its sweeping rejection of the possibility of knowing much about Jesus. The “progressive Christian” approach of Borg and his ilk, in its belief that whatever is of value in Christianity can be retained while it is detached from any historical roots, is surely misguided.

While Borg’s own commitment to the life of the Church and the Christian community is undoubtable – he became an Episcopalian and was a faithful churchgoer – it is hard to see his nuanced and subtle reading of the Bible attracting many to the cause. There is much of value in his work, but perhaps his greatest contribution to theology was in strengthening and refining the faith of orthodox believers who had to answer his objections.

Source: Christian Today